Staff Morale in Schools: How Culture, Leadership and Staff Drive Engagement

If you’ve been leading or working in a school over the past few years, you’ve probably felt it – the subtle, steady dip in energy, enthusiasm and connection. Teacher and staff morale isn’t a new challenge, but it’s one that remains under-researched and often overlooked in education.

Much of the existing research on educator wellbeing focuses on stress and burnout, especially in recent years (Converso et al., 2019; Senechal et al., 2016). Yet our Staff and Teacher Wellbeing Survey data continues to highlight morale as a pressing issue, with staff comments flagging both personal and organisational implications that warrant attention.

Part of the challenge lies in defining morale itself, and in understanding who is responsible for improving it. As Bost (2019) notes, morale is difficult to pin down precisely because it comprises so many interrelated components. This lack of clarity may explain why morale remains vastly understudied, despite its profound influence on school culture, educator wellbeing, student outcomes and the wider community.

Teaching and working in education is demanding intellectually, emotionally and physically, intensive and unrelenting (Sachs 2003). And while it may seem and feel like morale has sharply declined since the dawn of the pandemic, literature from the early 2000s shows that this downward trend has been decades in the making.

We, alongside researchers, argue that reform efforts over the last 30 years have failed to improve student achievement in schools because they overlooked the importance of culture and teacher morale within schools (DuFour & Eaker, 1998). More and more emphasis is being placed on teacher quality rather than on their working conditions; however, many researchers believe there is a relationship between the two (Houchard, 2005).

In this article, we explore:

- The Problem: Declining Teacher and Staff Morale

- What morale is and why it matters

- What influences staff morale

- The joint responsibilities of teacher and staff morale

- Impacts and solutions for boosting morale in schools

The Problem: Declining Teacher and Staff Morale

Staff morale is a growing challenge in many schools today. According to our Teacher Wellbeing Surveys, on average, only around 56% of staff across 65 Australian schools report high morale.

There are many reasons for this. Teaching has become increasingly complex and demanding. Educators are expected to meet diverse student needs, adapt to constant policy shifts and maintain high instructional quality (Evers, 2011). Over the past few decades, teacher morale has steadily declined as standardised testing, compliance and centralised control have taken priority in educational policy and school strategy (Ward, 2015; Bost, 2019). These challenges are further compounded by larger class sizes, escalating behavioural issues and reduced funding – all factors known to erode school climate and job satisfaction (Bost, 2019; Penfold, 2011).

This decline, however, is not new. For more than 30 years, teachers have reported feeling overloaded, undervalued and demoralised (Hicks, 2003; Mackenzie, 2004; Smyth, 2001). Lumsden (1998) noted that morale declines when teachers are stretched too thin and responsibilities expand beyond teaching into roles resembling social work. A shift in public attitudes and negative media coverage have only deepened this crisis (Mackenzie, 2007). These recurring patterns suggest that morale issues are systemic rather than situational.

While many educational reforms aim to improve student and school outcomes, they often overlook a critical factor: the capacity and morale of the people expected to actually implement changes, initiatives and reform. When teachers and staff lack energy, support and hope, even the most well-intentioned strategies falter. Long-term pressure has left many educators struggling to maintain the optimism required to sustain improvement.

Low morale doesn’t just affect individual wellbeing; it ripples across entire schools. It contributes to teacher attrition, absenteeism and emotional disengagement from students. Disheartened teachers may lower expectations, withdraw effort and unintentionally influence their colleagues’ attitudes, shaping a negative staff culture (Senechal et al., 2016). Since the success of any education system depends on the quality and commitment of its people, morale is not a “nice to have,” it is fundamental.

Improving morale requires more than wellbeing afternoons or tokenistic recognition. Motivation, effort and job satisfaction are directly linked to morale (Din et al., 2019). Teachers need supportive environments that value their work, enable meaningful contribution and remove unnecessary barriers (Bantwini, 2018; Govindarajan, 2012). Without this, systemic challenges continue to erode commitment, wellbeing and performance. Morale cannot be improved through quick fixes such as pep talks, reward- and-recognition days, or one-off initiatives. It requires consistent leadership, psychological safety, fair workload expectations, relationships and trust (Hess & Johnson, 2010) and, of course, collective effort towards lasting change.

What is Morale?

Morale is a complex, multi-dimensional concept without a single universally accepted definition (Sabin, 2015). Broadly, it reflects how individuals and groups feel about their work, their workplace and their capacity to succeed within it. Staff morale integrates mindset, motivation, satisfaction and alignment between personal needs and organisational goals (Hess & Johnson, 2010).

Individual morale is commonly defined as a mental or emotional state characterised by confidence, optimism, motivation and a willingness to persist (Hess & Johnson, 2010; Mendel, 1987). It is not a fleeting emotion, but a broader sense of purpose, hope and satisfaction. High morale requires energy, coherence, agency and a belief that one’s efforts make a difference (Hart et al., 2000). This is why morale cannot be lifted through isolated “feel-good” activities – it grows from sustained conditions that foster meaning, connection and purpose, not from temporary moments of cheerfulness.

Collective or staff morale goes beyond individual feelings. It is shaped by shared beliefs, relationships, norms and the tone of the workplace (Converso et al., 2019; Peterson et al., 2008). Zeitz (1983) defines morale as a collective emotional response to the organisation. Others associate it with collegiality, hope, trust, persistence and collective efficacy (Senechal et al., 2016). Importantly, morale is contagious. Both positive and negative attitudes can spread quickly within a staff group (Hess & Johnson, 2010), underscoring the collective responsibility all school staff have for maintaining and building up morale.

In schools, teacher/staff morale is described as the enthusiasm, professional interest and sense of purpose teachers and staff bring to achieving shared goals (Bentley & Rempel, 1980; Converso et al., 2019). It influences how school staff feel about their work, their colleagues and the school’s values.

Overall, morale is best understood as a long-term condition, shaped by the interplay of individual mindset, group culture and broader systemic conditions. To enhance staff wellbeing, morale is an important area to explore and analyse concurrently. Without it, initiatives aimed at improving staff wellbeing struggle to take root and sustain.

Why Morale Matters

Conversations about teacher and staff wellbeing often focus on stress, burnout and attrition. While these realities are important, they can overshadow an equally powerful truth – high staff morale is one of the greatest assets a school can have. High staff morale fosters pride, trust and commitment amongst staff. Low morale produces cynicism, reduced effort, absenteeism and ultimately, a decline in student outcomes (Black, 2001; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011).

When morale is strong, schools become places where staff feel valued, connected and motivated, and where students experience the flow-on benefits of stability, enthusiasm and high-quality teaching and learning. When school environments are healthy and morale is high, staff feel good about themselves, their colleagues and their work. They arrive at school with a sense of purpose and leave with a sense of accomplishment (Hoy & Miskel, 1987; Mackenzie, 2007). Research shows that positive staff morale independently contributes to teacher wellbeing and is strongly linked to healthier organisational climates and improved staff health outcomes (Hart et al., 1995; Converso et al., 2019).

Morale is not a “feel-good extra,” it is a professional performance driver. Teachers with high morale invest more energy into lesson planning, persist longer through challenges, build stronger relationships with students and colleagues, and show greater optimism and resilience. They are also more likely to stay in the profession, contribute to collective growth and mentor others (Din et al., 2019; Bantwini, 2018).

The benefits of strong staff morale extend far beyond the staff. When morale rises, student achievement rises with it. Motivated staff cultivate and contribute towards motivated classrooms. They set higher expectations, provide better feedback, and create safe, caring and aspirational learning environments. Research consistently links teacher morale to positive student attitudes, stronger academic outcomes, improved behaviour and greater engagement (Lumsden, 1998; Andrews, 1985; Miller, 1981). Likewise, schools with a positive climate report closer staff-student relationships, enhanced social and emotional skills and stronger community trust (Keiser & Schulte, 2009; Penfold, 2011).

What Influences Teacher and Staff Morale?

Morale is not shaped by a single factor. It is the result of personal, professional, organisational and societal influences working together. While much literature highlights the causes of low morale, such as excessive workload, poor leadership, limited resources, student behaviour challenges and greater accountability pressures, understanding these influences is not about dwelling on deficits, but about identifying where positive impact can be made.

Researchers have long recognised that teacher and staff morale is influenced by physical, emotional and attitudinal factors (Mackenzie, 2007). Teachers and staff frequently report experiencing pressure from large workloads, limited autonomy, insufficient classroom resources, poor student behaviour, administrative bureaucracy, a lack of voice in decision-making and few opportunities for career progression (Chen & Miller, 1997; Evans, 1998). Perceptions of low professional status, salary concerns and diminishing community respect also play a role (Buckingham, 2003; Evans, 1998). When emotional or physical exhaustion is left unaddressed, it can lead to disengagement, absenteeism, conflict and, ultimately, a decline in overall school performance (Hess & Johnson, 2010).

A thematic analysis of comments from our Staff Wellbeing Surveys revealed several recurring themes influencing the current state of staff morale:

- Leadership-related challenges

- High workload

- Staff negativity

- Poor communication

- Difficult/challenging student behaviour

- Staff conflict, gossip and/or cliques

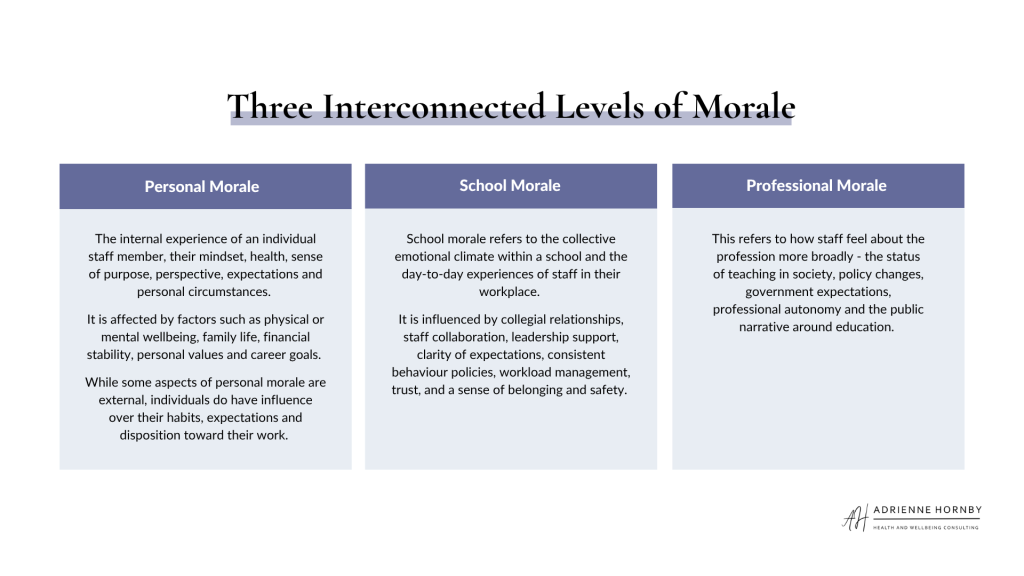

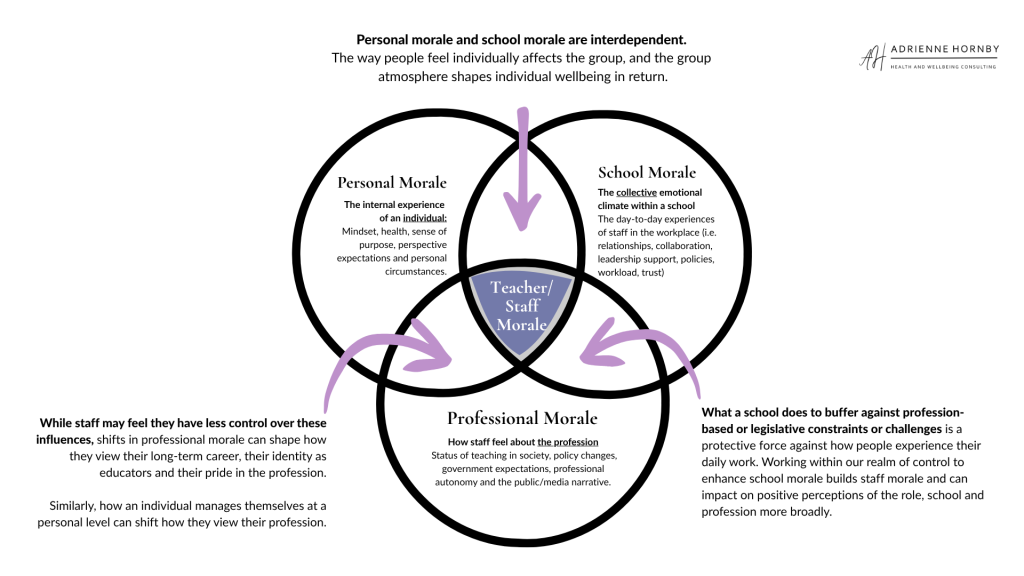

As explored earlier, morale is more than individual resilience or attitude; it is both personal and collective. Evans and Senechal et al. (2016) remind us that morale cannot be understood without considering both the individual and the school environment in which they work. Mackenzie (2007) helps make this complexity tangible by breaking morale into three connected levels: personal, school and professional morale. Together, these form an individual’s overall experience of teacher morale.

Key takeaway: Personal Morale + School Morale + Professional Morale = Teacher/Staff Morale (Mackenzie, 2007)

These levels overlap and influence each other. For example, a supportive school can buffer the impact of negative media or policy pressures, while strong personal morale can help individuals navigate challenging workplace climates. Equally, unresolved pressure in any one domain can erode the others.

What Specifically Shapes School Morale?

While morale is influenced by a complex mix of personal, school and professional factors, research consistently shows that the school environment plays a decisive role in shaping how teachers and staff feel day to day. It is within the school walls, not policy documents or public debates, that morale is either strengthened or slowly eroded.

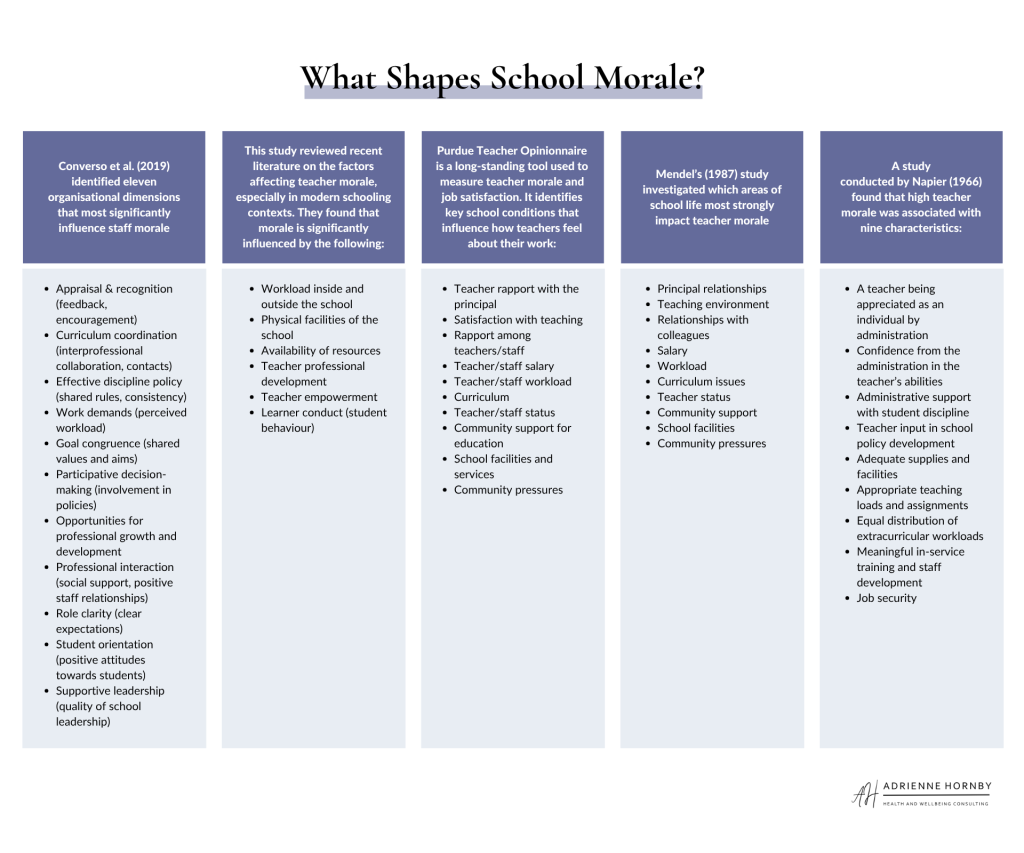

Research has identified specific elements within a school that consistently influence staff morale, outlined in the table below.

When conducting a thematic analysis of the comments provided related to the state of morale, in schools where staff view staff morale as high, the top themes associated with high morale are:

- A positive working environment

- Supportive colleagues

- Strong collegiality and teamwork

- Supportive leadership

- Strong staff relationships

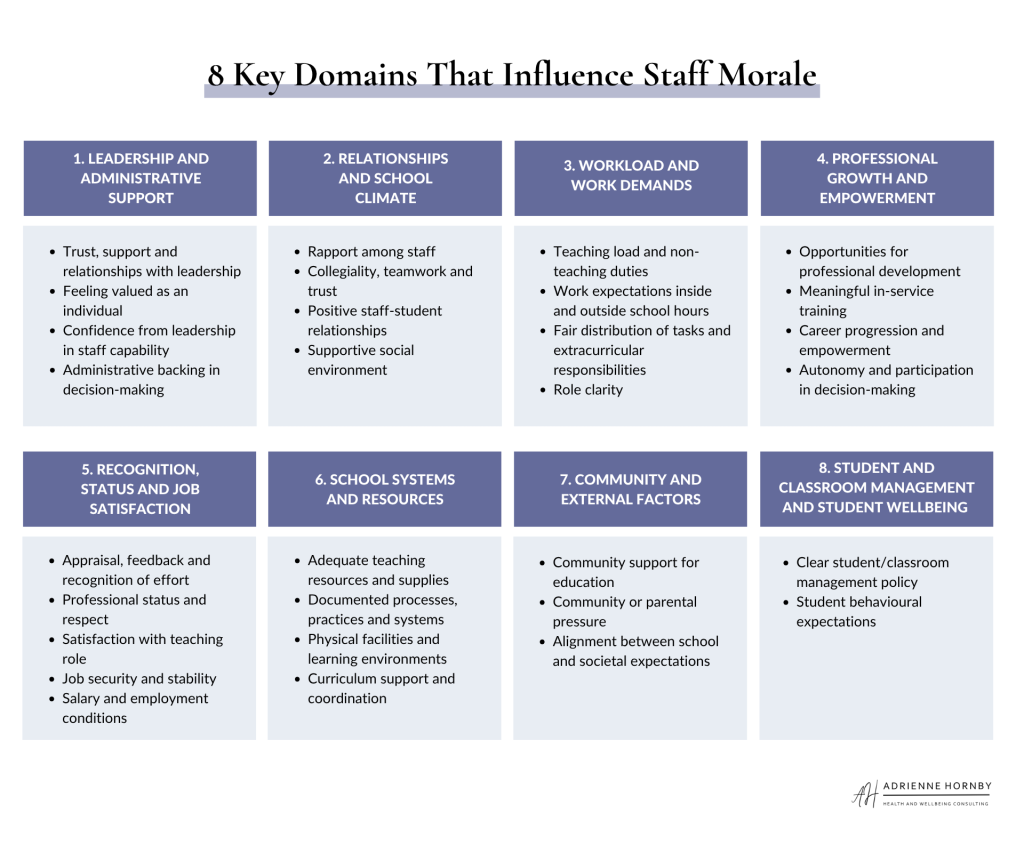

Across decades of research and a review of this literature,eight key domains emerge as the most significant influences on teacher and staff morale. These areas provide a practical lens for school leaders and teams to reflect, diagnose strengths and challenges, and design meaningful action, not quick fixes. They are outlined in the graphic below and will be discussed in detail in the following sections of this article.

1. Leadership and administrative support

Leadership shapes the daily conditions of teacher work and strongly predicts morale. Principals, senior leaders and middle leaders influence culture, fairness, workload settings and autonomy; their visibility, recognition and communication practices matter (Miller, 1981; Ma & MacMillan, 1999; Mackenzie, 2007; Senechal et al., 2016). High-morale schools feature leaders who communicate policy rationale clearly, are aligned in their messaging and vision, invite teacher voice and buffer and shield unnecessary administrative burden. Across nearly all literature sources, the findings identify leadership at school and system levels as pivotal to morale (Mackenzie, 2007).

Possible solutions:

- Open, two-way communication and visible, accessible leadership help ensure more decentralised and inclusive decision making

- Explain policy and strategic rationale consistently and transparently to build coherence and trust

- Establish, maintain and sustain trust through rapport building and clear leadership team alignment in vision and goals

- Address and ensure fairness and equity in workload, opportunities and expectations across teams and staff

- Ongoing support and development for principals, senior leaders and middle leaders as culture-shaping agents

2. Relationships and school climate

Climate and culture are the everyday “feel” of school life and powerfully influence health, productivity and morale (May & Sanders, 2013; Syahril & Hadiyanto, 2018; Orsi et al., 2016; Mboweni & Taole, 2022). Culture reflects shared norms, values, rituals and relationships that reinforce collective purpose (Deal & Peterson, 1998; Bost, 2019). Cohen, McCabe, Michelli, and Pickeral (2009) stated that school culture consists of five areas: safety, relationships, physical environment, shared vision and participation.

Improvement is strongest when the school is aligned with its strategic direction and when there is a perceived and experienced supportive and shared culture (Kaplan & Owings, 2013; Bost, 2019). Positive climates correlate with stronger student motivation and achievement and collective efficacy (Sackney, 1998; Fyans & Maehr, 1990; Bost, 2019) and can be built in any context, regardless of socioeconomic status (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Bost, 2019). Relational trust among staff, students and leaders sustains engagement even under workload pressure (Senechal et al., 2016).

Possible solutions

- Offer meaningful relationship and team-building opportunities to enhance social connections and a sense of belonging

- Create time and structures for collaboration, collegial support and learning partnerships (such as Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), Inquiry and/or Action Learning Projects) (Gruenert & Valentine, 1997; Bost, 2019)

- Establish clear, co-created norms for safety, relationships, communication, shared vision and participation (Cohen et al., 2009; Bost, 2019)

- Build relational trust intentionally through consistent communication and follow-through (Senechal et al., 2016)

3. Workload and work demands

Intensifying workload, administrative tasks, constant initiatives and accountability pressures erode morale and job satisfaction (Sachs, 2003; Hoyle, 2001; Mackenzie, 2007; Senechal et al., 2016). Time constraints fuel exhaustion and reduce satisfaction (Chen & Miller, 1997; Bost, 2019). Teachers describe overload in concrete terms, too many classes, excessive paperwork and competing demands, which undermines perceived quality and balance of teaching and learning practices (Senechal et al., 2016). Over-emphasis on compliance, data collection and reporting can displace planning and instruction.

Possible solutions

- Audit workload; for every new initiative added, remove an equivalent demand. Utilise the Workload Reduction Toolkit to optimise workload management (AITSL, 2021)

- Protect planning time and streamline data/reporting to prioritise instructional value (Senechal et al., 2016)

- Slow the pace of change and coordinate initiatives to reduce duplication and drift (Mackenzie, 2007)

- Review class sizes, duty allocations and non-teaching load with explicit equity checks (Senechal et al., 2016)

- Provide role clarity to all staff to understand not only their roles and expectations, but also to provide clarity on the responsibilities of other leaders and staff

4. Professional growth and empowerment

Morale rises when professional learning is targeted, relevant, empowering and aligned to teachers’ needs and goals. Conversely, poorly designed and delivered PD lowers morale (Govindarajan, 2012; Bosso, 2017; Potolea & Toma, 2015; Postholm, 2012). High-quality development strengthens self-efficacy, professional identity and practice throughout a teacher’s career (Nugroho et al., 2020; Hattie, 2012).

Teacher and staff efficacy (the belief in one’s capacity to enable student success) predicts the quality of planning, resilience and supportive practice (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001; Hattie, 2012). This sense of efficacy develops through mastery experiences, vicarious learning, constructive feedback and effective emotional regulation (Bandura, 1997; Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998). Importantly, when teachers and staff have a voice in decisions that affect their work, their sense of efficacy, and consequently, their morale, increases even further (Hattie, 2012; Senechal et al., 2016).

Possible solutions

- Co-design PD with staff; align to real needs and subject contexts (Bosso, 2017; Postholm, 2012)

- Offer flexible, self-directed pathways and career progression options (Potolea & Toma, 2015; Nugroho et al., 2020)

- Build teacher leadership and decision-making roles to strengthen agency and efficacy (Hattie, 2012; Senechal et al., 2016)

- Use coaching, observation and feedback focused on growth, not just compliance (Hattie, 2012; Senechal et al., 2016)

5. Recognition, status and job satisfaction

Timely feedback, appreciation and visible respect are consistently linked to higher morale (Huysman, 2008; Mackenzie, 2007; Reed, 2010; Andrews, 1985; Willis & Varner, 2010). Recognition matters – and often, promotions elevate morale more through recognition of contributions than through pay (Hess & Johnson, 2010). Conversely, media narratives that spotlight problems while ignoring daily successes depress morale and erode the perceived status of the profession (Mackenzie, 2007). Pay also remains a potent factor in status and satisfaction, particularly when rising workloads are not met with fair compensation (Mackenzie, 2007; Bost, 2019; Senechal et al., 2016).

Possible solutions

- Formal and informal recognition of effort and impact; clear reward systems (Hess & Johnson, 2010; Senechal et al., 2016)

- Implement fair, transparent appraisal and recognition systems that value effort and impact (Andrews, 1985; Willis & Varner, 2010)

- Advocate and share positive stories to counter negative media effects on status (Mackenzie, 2007)

- Clarify career structures and advancement opportunities and pathways (Hess & Johnson, 2010; Mackenzie, 2007)

- Monitor alignment between workload and remuneration; surface and address inequities early (Senechal et al., 2016)

6. School Systems, Processes and Resources

Clear and consistent school systems are essential to maintaining staff morale. It is not only the physical resources that matter, but the coherence of the structures, policies and processes that guide daily work. When systems such as behaviour management, curriculum coordination, communication, assessment and policy implementation are well-defined, consistently applied and supported by leadership, staff experience greater certainty, trust and instructional focus (Kaplan & Owings, 2013; Gruenert & Valentine, 1997).

Staff are more engaged and confident when there are coordinated systems for curriculum planning, resource access, student welfare and data use, rather than fragmented processes or excessive bureaucratic demands. Coherent practices, processes and policies allow staff to focus less on administration and red tape and more on teaching, relationships and wellbeing (Senechal et al., 2016).

Possible solutions

- Establish and maintain clear, consistently applied school-wide policies and processes that are regularly reviewed and adhered to by leaders, teachers and staff

- Ensure policies are coherent, explained clearly and aligned to school values and practice (Senechal et al., 2016)

- Allocate time for curriculum coordination, planning and shared practices (Kaplan & Owings, 2013)

- Reduce procedural ambiguity by documenting expectations and ensuring equitable application

7. Community and external factors

Parent and community engagement boosts teacher satisfaction, school reputation and student outcomes (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011; Sapungan & Sapungan, 2014; Shahid, 2018; Hornby & Blackwell, 2018). While socioeconomic status pressures can heighten complexity, the research tells us that positive climates are achievable in any context (Berkowitz et al., 2016; Bost, 2019).

Possible solutions

- Develop a parent engagement strategy that supports learning partnerships and clear two-way communication (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011; Sapungan & Sapungan, 2014)

- Communicate policy purposes and school expectations to families and the community to build alignment (Senechal et al., 2016)

- Proactively share school successes to strengthen external perceptions and professional status (Mackenzie, 2007)

8. Student behaviour and diverse learning needs

Student wellbeing and behaviour management challenges are a major driver of reduced staff morale. School staff frequently identify student behaviour and complex learning needs as a key reason for stress and discouragement. Occupational violence in some schools can also have a profound impact on morale. Trauma or feelings that safety is compromised can reshape staff’s attitudes at work, reduce efficiency and destabilise the wider climate if left unaddressed (O’Connor & Mooney, 2014; Burk, 2010; Roberts et al., 2012; Mboweni, 2020; Mboweni & Taole, 2022).

The literature highlights perceptions that teachers are being expected to act as social workers while also meeting a wider range of learning needs (Lawrence, 1999; Buckingham, 2003; Hess & Johnson, 2010). Concurrently, meeting complex and diverse student learning needs is perceived as hindered when professional learning is misaligned or designed without teacher/staff consultation, which can limit classroom impact and feelings of efficacy.

Possible solutions

- Implement systemised, coherent, consistently applied behaviour and welfare systems with leadership backing (Buckingham, 2003; Hess & Johnson, 2010; Mboweni & Taole, 2022)

- Provide trauma-informed supports and post-incident care for staff and students (O’Connor & Mooney, 2014; Roberts et al., 2012)

- Post-incident support, debriefing and access to specialist services (O’Connor & Mooney, 2014; Roberts et al., 2012; Mboweni & Taole, 2022)

- Targeted, co-designed professional development on inclusion, de-escalation and differentiated instruction (Mboweni & Taole, 2022)

- Structured parent partnership strategies to support attendance, behaviour and learning plans (Mboweni & Taole, 2022)

- Tiered behaviour supports and clear classroom routines (Buckingham, 2003; Hess & Johnson, 2010)

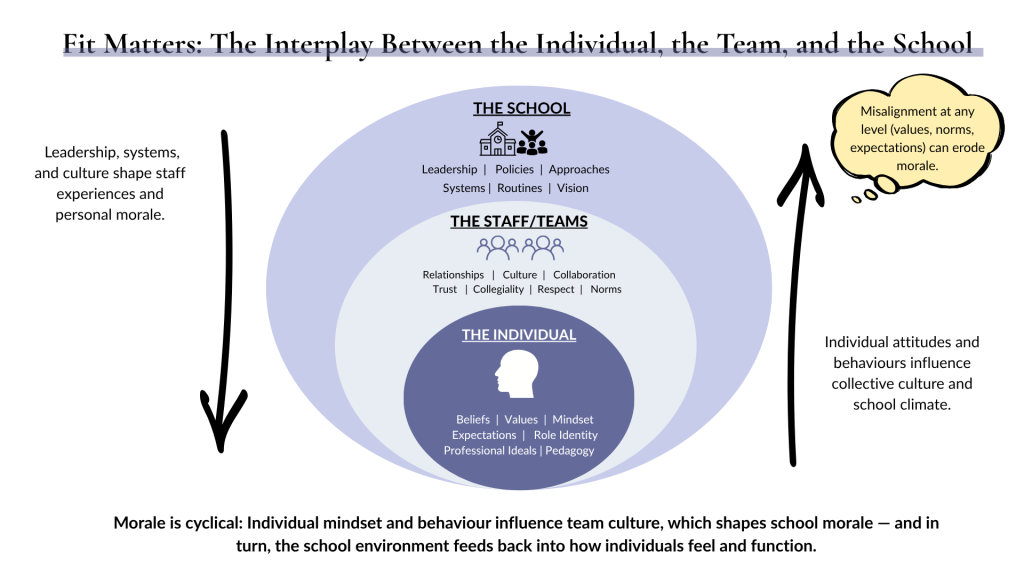

The Alignment Factor: Where School Culture Meets Personal Fit

Throughout this article, the emphasis has been on the role of schools (leadership, systems, culture and working conditions) in shaping staff morale. However, there is an important and often uncomfortable truth that must also be acknowledged: morale is not solely a school responsibility; it is shared. While schools must foster environments that support wellbeing and professionalism, individuals also bring their own beliefs, expectations, mindsets and behaviours into the workplace. To ignore this would be a disservice to both leaders and staff.

Every educator arrives with their own expectations of what “good teaching” looks like, what their work should involve, and how a school should operate. Schools, in turn, have their own vision, values, policies and constraints shaped by students, community context and leadership.

When there is alignment between the individual’s professional ideals and the school’s culture, morale is strengthened. When there is misalignment, morale suffers and not always because of failure, but because of poor fit. Some individuals may find that a particular school, or in some cases, the profession itself, does not match their expectations, values, or sense of purpose.

Senechal et al. (2016) identify several areas where alignment (or misalignment) between individual and school culture influences fit and morale:

- Fairness: How staff perceive workload distribution, recognition and decision-making

- Pedagogy: Alignment between an individual’s beliefs about teaching and the school’s instructional approach

- Organisational efficiency: Expectations around how smoothly systems, policies and routines operate

- Interpersonal relations: Quality of trust, care and respect between staff, students, leadership and parents

- Collegiality: Expectations around teamwork, collaboration and professional conduct

- Self-conception and role identity: How individuals see themselves as professionals compared to the roles the school requires them to play

Evans and Senechal et al. (2016) argue that when misalignment exists across one or more of these areas, teachers and staff can feel placed in a “compromised context,” where they are required to operate within a culture that conflicts with their professional identity. One or two areas of misfit may be tolerable if there is strong alignment elsewhere, but persistent and widespread misalignment erodes morale and engagement.

This raises an important point: low morale does not always signal failure of leadership; it may reflect a lack of alignment among some staff with their roles, teams, or schools. In such cases, it may indicate either the need for growth within the individual or transformation within the school environment – or both. Schools must create cultures in which teachers and staff can enact their professional purpose. At the same time, educators must also be willing to reflect, adapt and grow, both professionally and personally.

Conclusion

Teacher and staff morale is not a soft extra; it is the engine that drives school improvement and student outcomes. Our survey data and the literature converge on a simple logic: when culture, climate and working conditions enable people to do their best work, students learn more and school outcomes soar (Kraft & Papay, 2014; Adeogun & Olisaemeka, 2011; Bost, 2019).

Morale is multi-dimensional and shared. It is shaped by personal mindset, collective norms and system structures, and it rises where professional ideals meet supportive conditions (Hess & Johnson, 2010; Mackenzie, 2007). Quick fixes and one-off morale-boosting activities rarely endure. What truly sustains are approaches that acknowledge, address and prioritise strong leadership, staff collegiality, school culture, workload management, professional growth, recognition, satisfaction, systems, community and student wellbeing and management. When these conditions are present, teachers and staff report pride and accomplishment (Hoy & Miskel, 1987), remain longer in the profession (Gardner, 2010), grow more effective over time (Kraft & Papay, 2014) and model optimism that lifts student engagement and achievement (Lumsden, 1998; Andrews, 1985; Miller, 1981).

The Well-Led Schools Partnership Program provides a practical example of these principles in action. Schools participating in the program have shown measurable improvements in staff perceptions of morale, demonstrating that targeted leadership development, systemic support and cultural alignment can transform the school environment for both staff and students.

Finally, morale is malleable. Schools and their staff can redesign cultures and systems, and individuals can develop themselves, reflect, adapt and lead from their roles. Because high staff morale is cultivated, not chanced, and when it rises, everyone benefits: teachers, students and the wider school community.

References:

Adeogun, A. A., & Olisaemeka, B. E. (2011). The relationship between educational resources and students’ academic performance in secondary schools in Lagos State, Nigeria. International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies, 3(2), 41–47.

AITSL. (2021). Workload reduction toolkit. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. https://www.aitsl.edu.au

Andrews, R. (1985). Teacher morale and student achievement. The Clearing House, 59(1), 29–32.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bantwini, B. D. (2018). Teacher morale, job satisfaction and motivation in South Africa: Identifying the challenges and seeking solutions. South African Journal of Education, 38(1), 1–10.

Barth, R. S. (1990). Improving schools from within: Teachers, parents, and principals can make the difference. Jossey-Bass.

Bentley, R. R., & Rempel, A. M. (1980). Manual for the Purdue Teacher Opinionaire. Purdue Research Foundation.

Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2016). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669821

Black, S. (2001). Morale matters. American School Board Journal, 188(1), 40–43.

Bosso, D. (2017). Teacher motivation and job satisfaction in context: A comparative study of educators in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Educational Research Quarterly, 40(3), 3–27.

Bost, D. (2019). Factors that affect teacher morale. Ed.D. dissertation, Liberty University.

Buckingham, J. (2003). The rise and fall of Australia’s education standards. Centre for Independent Studies.

Burk, N. (2010). Teacher stress and student behaviour: Managing classroom challenges.

Chen, J., & Miller, P. (1997). Teacher stress and the future of teaching. Educational Review, 49(3), 293–302.

Cohen, J., McCabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180–213.

Converso, D., Cortini, M., Di Chiacchio, C., & Sanseverino, D. (2019). Organizational climate and teachers’ morale: Developing a specific tool for the school context – A research project in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology

Deal, T. E., & Peterson, K. D. (1998). Shaping school culture: The heart of leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Din, N., Akhtar, S., & Ehsan, N. (2019). Impact of teacher morale on teaching effectiveness and student achievement. Pakistan Journal of Education, 36(2), 79–100.

DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. ASCD.

Evans, L. (1998). Teacher morale, job satisfaction and motivation. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Evers, W. (2011). Teacher burnout and morale: A study of stress and resilience

Fyans, L. J., & Maehr, M. L. (1990). School culture, student ethnicity, and motivation. American Educational Research Journal, 27(4), 829–855.

Gardner, H. (2010). Truth, beauty, and goodness reframed: Educating for the virtues in the 21st century. Basic Books.

Govindarajan, M. (2012). Motivation and teacher performance in educational settings. ❓ Reference details not found in provided PDFs — please verify.

Gruenert, S., & Valentine, J. (1997). School Culture Survey. University of Missouri-Columbia.

Hart, P. M., Conn, M., & Carter, N. L. (2000). Teachers’ morale and school climate. Australian Educational Researcher, 27(3), 1–22.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

Hess, F. M., & Johnson, A. (2010). Learning on the job: Professional development in America’s schools. Harvard Education Press.

Hicks, D. (2003). Teacher workload and morale in UK schools

Hornby, G., & Blackwell, I. (2018). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An update. Educational Review, 70(1), 109–119.

Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37–52.

Houchard, M. A. (2005). Principal leadership, teacher morale, and student achievement in seven schools in Mitchell County, North Carolina. Doctoral dissertation, East Tennessee State University.

Hoy, W. K., & Miskel, C. G. (1987). Educational administration: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Random House.

Hoyle, E. (2001). Teaching: Prestige, status and esteem. Educational Management & Administration, 29(2), 139–152.

Huysman, J. R. (2008). Rural teacher satisfaction: An analysis of beliefs and attitudes of rural teachers’ job satisfaction. The Rural Educator, 29*(2), 31–38.

Kaplan, L. S., & Owings, W. A. (2013). Culture re-boot: Reinvigorating school culture to improve student outcomes. Corwin Press.

Keiser, K. A., & Schulte, L. E. (2009). Seeking the sense of community in schools. International Journal of Learning, 16(9), 623–636.

Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2014). Can professional environments in schools promote teacher development? Explaining heterogeneity in returns to teaching experience. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(4), 476–500.

Lumsden, L. (1998). Teacher morale. ERIC Digest, 120. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED422601.pdf

Ma, X., & MacMillan, R. B. (1999). Influences of workplace conditions on teachers’ job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Research, 93(1), 39–47.

Mackenzie, N. (2004). Teacher morale: Some factors shaping the climate of work in schools

Mackenzie, N. M. (2007). Teacher morale: More complex than we think? Australian Journal of Education, 51(2), 135–149.

May, D., & Sanders, E. (2013). Teacher morale in primary schools. Educational Review, 65(2), 232–247.

Mendel, P. C. (1987). An investigation of factors that influence teacher morale and satisfaction with work conditions. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon.

Miller, R. (1981). Staff morale, school climate, and educational productivity. Educational Leadership, 38(6), 483–486.

Mboweni, I. (2020). Teachers’ perceptions of workplace safety and morale in South African schools. ❓ Reference details not found in provided PDFs — please verify.

Mboweni, I., & Taole, M. (2022). Teachers’ experiences of school violence and its impact on morale. South African Journal of Education, 42(1), 1–10.

Napier, R. W. (1966). Teacher morale and student achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 50(316), 12–17.

Nugroho, A., Davis, S., & Lopez, J. (2020). Professional development that empowers teachers: Evidence from Asia-Pacific. Australian Council for Educational Research.

O’Connor, P., & Mooney, A. (2014). Violence against teachers: Impacts on morale and practice.

Orsi, M., et al. (2016). Teacher motivation and school climate in Italy

Penfold, A. (2011). Teacher wellbeing and workplace climate in Australian schools

Peterson, K. D., et al. (2008). Improving teacher morale through school culture

Postholm, M. B. (2012). Teachers’ professional development: A theoretical review. Educational Research, 54(4), 405–429.

Protheroe, N. (2006). Maintaining high teacher morale. Principal, 86(1), 46–49.

Reed, K. (2010). Recognition and teacher motivation.

Roberts, R., et al. (2012). Workplace aggression in schools: Effects on teachers’ morale

Sabin, M. (2015). Understanding teacher morale among primary school teachers. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(10), 125–135.

Sachs, J. (2003). The activist teaching profession. Open University Press.

Sackney, L. (1998). Building organizational learning communities in schools. Canadian Journal of Education Administration and Policy, 6, 1–17.

Sarason, S. B. (1996). Revisiting “The culture of the school and the problem of change.” Teachers College Press.

Sapungan, G. M., & Sapungan, R. M. (2014). Parental involvement in child’s education: Importance, barriers and benefits. Asian Journal of Management Sciences & Education, 3(2), 42–48.

Senechal, T., et al. (2016). Understanding teacher morale among primary school teachers. Virginia Commonwealth University, Metropolitan Educational Research Consortium.

Shahid, S. (2018). The impact of parental involvement on student success in Pakistan

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and self-efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038.

Smyth, J. (2001). Teachers’ work in a global era: Labour and professionalism. Falmer Press.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk Hoy, A., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068002202

Ward, L. (2015). Teacher workload and morale: A study of contemporary challenges in education.

Willis, J., & Varner, L. (2010). Factors that affect teacher morale. Academic Leadership: The Online Journal, 8(4), Article 65. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj/vol8/iss4/65

Zeitz, G. (1983). Structural and individual determinants of organizational morale and satisfaction. Social Forces, 61(4), 1033–1058. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578271

From the blog

Who Really Shapes Morale in Schools | Season 4: Episode 1

If you’ve ever felt the energy dip at school or amongst your team (or yourself!), you already know this episode isn’t about “morale boosters” or…

Teacher Wellbeing: The State of the Nation and The Solutions Our Teachers Want Moving Forward

Teacher wellbeing is not just a personal issue; it’s a professional necessity. It’s closely tied to educator success and student outcomes, and a lack of…

Staff Morale in Schools: How Culture, Leadership and Staff Drive Engagement

If you’ve been leading or working in a school over the past few years, you’ve probably felt it – the subtle, steady dip in energy,…